Rethinking T2050: Aligning Phoenix’s Transportation Funding with Safety and Equity

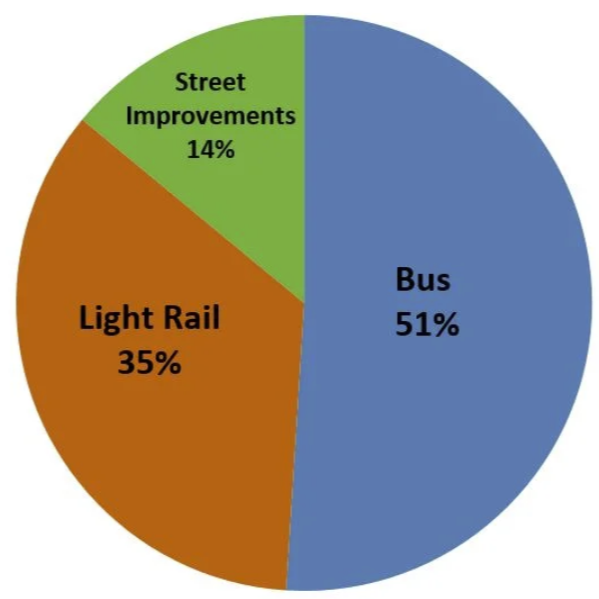

When Phoenix voters approved the Transportation 2050 (T2050) sales tax in 2015, it was promoted as a balanced, multimodal plan to improve bus service, expand light rail, and fund street improvements across the city. The 35-year program, supported by a 0.7% city sales tax (increased to 1.2% in 2024), is projected to generate about $16.8 billion in local revenue and roughly $31.5 billion in total funding when combined with federal, regional, state, farebox, and financing sources.

Nearly a decade later, however, questions remain about how well T2050 investments align with Phoenix’s Vision Zero goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries, as well as with the city’s broader Climate Action Plan objectives.

The Current Challenge

Phoenix continues to face some of the highest traffic fatality rates in the nation, with pedestrians and cyclists disproportionately represented in deaths and serious injuries (Cronkite News). The City of Phoenix’s 2024 High Injury Network (HIN) includes less than 1% of streets yet accounts for 11% of all serious injury and fatal crashes.

Despite these realities, the 14% labeled “street improvements” in T2050 is not broken down by mode. In reality, much of it supports road resurfacing, widening, and auto-capacity projects, while bike lanes, sidewalks, and safety countermeasures get only a fraction. Even when road dollars are available, they typically aren’t used to proactively add protected bike lanes or pedestrian safety improvements; they’re tied to street resurfacing or “capacity” projects, which benefit vehicles first. We see this with HURF funds and with projects like the 35th Avenue Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line, which was pitched as a transformative investment but has dragged on for years and is still being designed without basics like bike lanes.

Decades of research show that adding lanes induces more driving, increases speeds, and ultimately leads to more crashes (Duranton & Turner 2011; FHWA 2020). At the same time, relatively low-cost but high-impact interventions — such as high-visibility crosswalks, protected bike lanes, and safer mid-block crossings near transit stops — often struggle to gain traction, even though they directly target the city’s most dangerous streets.

Case Study: 35th Avenue BRT

The upcoming 35th Avenue Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line illustrates how T2050 dollars can miss opportunities for multimodal safety. At a recent community meeting, a project consultant stated that bike lanes would not be included on 35th Avenue because “there aren’t bike lanes there today.”

This logic highlights a structural issue: rather than using T2050 and BRT investments to fill gaps in the multimodal network, design decisions often default to existing conditions. As a result, even once-in-a-generation investments can perpetuate the absence of safe bicycle facilities along high-crash streets.

Oversight: The Citizens Transportation Commission

The Citizens Transportation Commission (CTC) was created by Phoenix voters as part of T2050 to provide public oversight of how the funds are spent. The commission is composed of residents appointed by the Mayor and City Council, representing each council district and the mayor’s office.

In theory, the CTC reviews T2050 allocations, monitors spending, and makes recommendations to City Council. Its meetings are open to the public and intended as a check on staff-driven priorities.

However, concerns have emerged about the effectiveness of CTC oversight. For example, despite broad community support for the McDowell Road Revitalization project — which proposes protected bike lanes and multimodal improvements along a key corridor — the CTC has not allocated funding to advance the project. This omission is notable given McDowell’s role in the High Injury Network and its alignment with Vision Zero and climate goals.

Comparable City Plans

In Nashville, the “Choose How You Move” referendum passed in November 2024. It adds a 0.5 % sales tax surcharge to fund a $3.1 billion transportation improvement program, focused on expanded bus service, sidewalks, synced traffic signals, and safety enhancements. The plan is slated for rollout over 15 years. (Axios Nashville)

Seattle’s Sound Transit 3 (ST3) is a more expansive, $54 billion regional plan pursuing light rail, commuter rail, and bus rapid transit—far exceeding Phoenix’s T2050 in scope but also serving a broader metropolitan area rather than just one city. (2017 Sound Transit Financial Plan) Phoenix Road Safety Overview.” 2024.

Atlanta’s "More MARTA" (2016) invested $2.7 billion over 40 years through a half‑cent sales tax for transit expansion (More Marta Atlanta)

Los Angeles County (Measure R, 2008 & Measure M, 2016) Together, these sales tax measures are expected to generate nearly $160 billion combined for transit, rail, highways, and local return over 30–40 years (Move LA)

The Mobility Equity Program

The Equity-Based Transportation Mobility Equity (EBTM) Program was established to ensure that historically underinvested neighborhoods — particularly in South Phoenix and Maryvale — receive targeted transportation improvements. In addition to T2050, it also received funding through the Phoenix 2023 GO Bond.

Despite this additional funding and significant consultant spending to develop regional recommendations, there has been little visible progress. Residents in program areas report a lack of tangible improvements such as safer crossings, sidewalks, or bike connections.

This raises questions about program accountability. Without clear timelines or delivered projects, the Mobility Equity Program risks becoming another study-driven effort without measurable outcomes, despite being designed to serve the very communities most impacted by traffic violence.

The Urban Phoenix Project will dig into the EBTM Program and expose its many shortcomings in a forthcoming blog post.

Equity and the Road Safety Action Plan (RSAP)

The Road Safety Action Plan (RSAP), adopted by Phoenix in 2022, is the city’s central framework for achieving Vision Zero. The plan identifies strategies to eliminate traffic deaths and serious injuries, maps the High Injury Network, and commits to publishing annual reports each June to track progress.

These reports are intended to provide transparent data on fatalities, serious injuries, and implementation outcomes, including how equitably investments are distributed.

This year, however, the RSAP draft has been delayed and withheld from both the Vision Zero Community Advisory Committee and the public. Because the RSAP is the city’s primary accountability tool for Vision Zero, withholding it undermines public oversight and makes it impossible to evaluate whether programs like the Mobility Equity Program or T2050-funded projects are achieving safety outcomes.

Equity was meant to be a cornerstone of the RSAP, ensuring investments flowed first to the communities most affected by traffic violence. Yet with the RSAP unpublished and the Mobility Equity Program showing little progress, Phoenix risks falling short on its equity commitments.

Proven Safety Investments

Research consistently demonstrates the effectiveness of multimodal safety improvements that could be prioritized under T2050:

Protected Bike Lanes & Complete Streets: Reduce cyclist injury risk by up to 90% compared with unprotected streets (Lusk et al., Injury Prevention, 2011).

High-Visibility Crosswalks & Stop Bars: Increase driver yielding and reduce crashes, with RRFB-equipped crossings seeing yielding rates up to 98% and high-visibility school crosswalks reducing crashes by 37% (FHWA, Every Day Counts, 2023; FHWA evaluation of school crosswalks, 2010).

Leading Pedestrian Intervals (LPIs): A before-and-after study of 10 intersections in State College, Pennsylvania, demonstrated a 58.7% reduction in pedestrian–vehicle crashes at sites where LPIs were implemented (Fayish & Gross, 2010)

These are relatively low-cost measures compared to roadway expansion, yet remain limited in scale given the size of the T2050 budget.

Looking Ahead

At the city level, Phoenix’s T2050 stands out as one of the most ambitious long-term transportation funding commitments in the United States, with a budget more than ten times larger than Nashville’s recent plan. By comparison, regional efforts such as Seattle’s Sound Transit 3 or Los Angeles County’s Measures R and M exceed T2050 in scale. Still, they are designed to serve entire metropolitan regions, not a single city.

T2050 is therefore remarkable not only for its size but also for the level of commitment a single city has made to multimodal transportation funding over multiple decades.

As Phoenix continues to invest billions through T2050, the alignment between funding allocations, Vision Zero, and the Climate Action Plan will determine whether the city moves toward safer, more sustainable streets.

The 35th Avenue BRT project, the lack of funding for McDowell Revitalization, and the stalled Mobility Equity Program all illustrate how multimodal opportunities are being missed — not because funding doesn’t exist, but because decision-making processes prioritize the status quo.

The research is clear: shifting even a modest share of T2050 dollars toward proven multimodal safety treatments could significantly reduce fatalities, support climate goals, and address longstanding inequities in neighborhoods most affected by traffic violence.